ONDC - A solution that will create many problems

You cannot "tech" your way through every real world challenge

In 1950, Frank McNamara noticed a problem. He was at a restaurant and found that he had forgotten his wallet back home. This gave birth to the idea of a charge card. Wealthy customers could charge their expenses to the card and pay for it at the end of the month.

He started a network called the Diners Club. This gave birth to a new industry called the Revolving credit industry which we today call the credit card industry.

Banks saw the rise of the Diners Club and thought they needed to get in on the act. The purpose of a bank is to lend. This is the best kind of lending. Small sums, high volume, high interest, high throughput, the holy grail of finance.

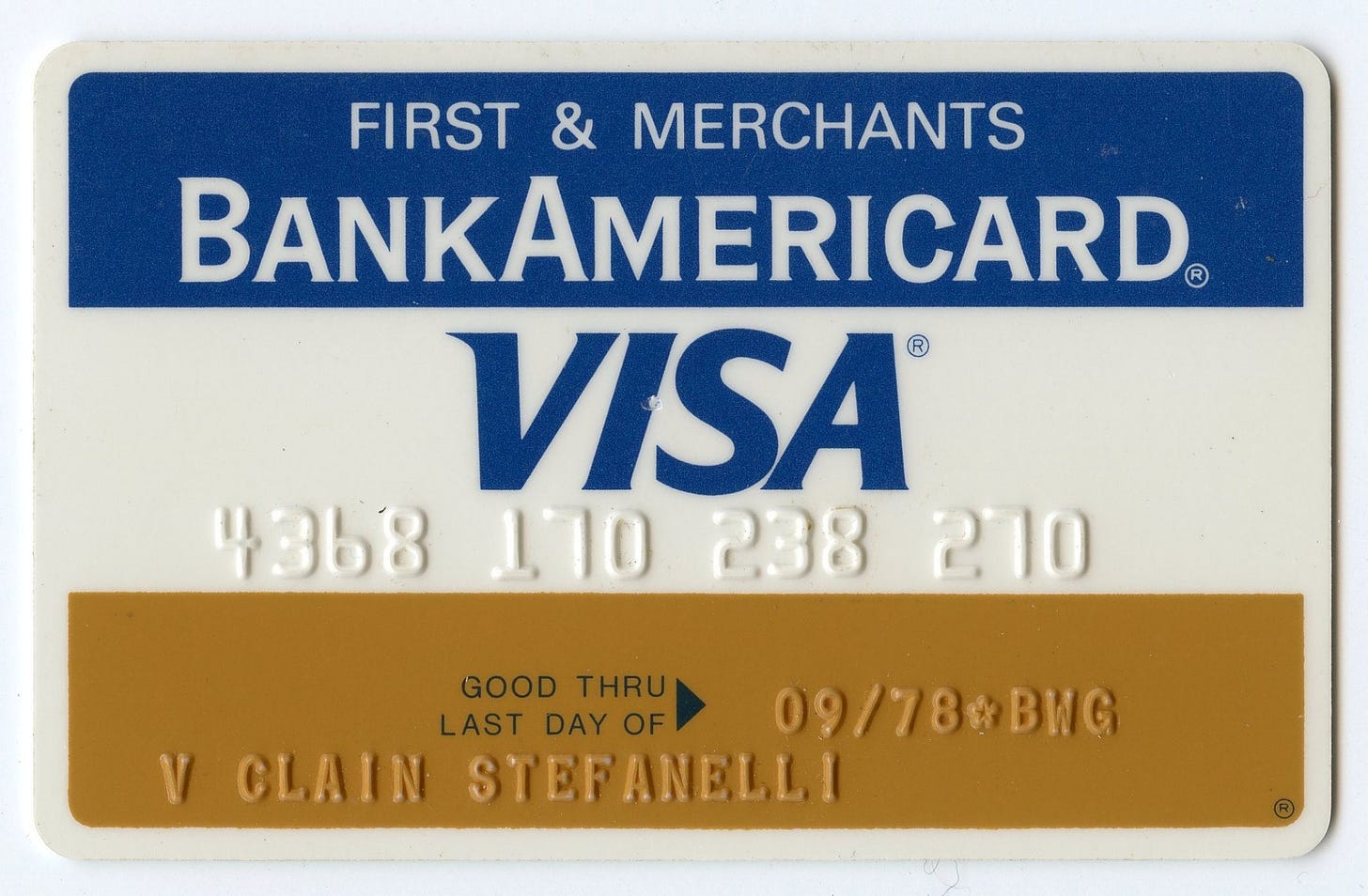

One of the banks that went after this business was Bank of America and in the late 50s they launched “Bank Americard”. They started an experiment in Fresno, California and distributed the cards to all of their customers. The experiment worked and soon they expanded this card distribution all over California. And like that, the police were introduced to a new kind of crime - Credit card fraud.

Playing loose and dirty, Bank of America had managed to corner a huge market share but had a 22% delinquency rate, not to mention the frauds. Joseph Williams who masterminded the Bank Americard was promptly fired.

A few of his associates decided to clean up the program and put financial controls in place. By late 1960, the program was profitable but Bank of America let the perception of troubles linger so that no new competitor got interested in the sector.

In 1970, they decided to open up the program for other banks to participate. A manager at a participating bank Dee Hock identified that there needed to be an independent company that managed the rails. That way, all the banks could participate in the wealth creation opportunity. Bank Americard was spun out into a separate entity. Eventually, in 1974, BankAmericard along with Chargex, Barclaycard and others would come together to create a single internationally accepted network for money movement called Visa.

What they provided in essence was a trust layer for money movement.

This layer was insanely complicated back in the 60s when computer penetration was basic at best, but with greater computerisation, it became easier to run and scale this layer.

Today nobody from Visa visits any of the stores to ensure that the operations are run smoothly.

When you come to a country like India, one of the problems is micro-transactions. Traditionally, Visa would charge 5 cents and a 1.5% commission. But what is the transaction itself is 10 cents. While Visa did localise, this was insufficient.

India created a body called NPCI to take care of the needs of the country. They successfully created National Electronic Fund Transfer (NEFT) and Real-time Gross Settlement (RTGS). Then they meandered through a series of missteps including Mobile Money Identification (MMID) and finally pivoted that system to arrive at Unified Payments Interface (UPI).

In 2015, Paytm which had started merely as a phone recharge business was ruling the micro-transaction market with their wallet. Their success was in no small part paved through insane customer service. If your transfer was not processed or hung, all you had to do was drop a tweet. An actual human would respond to it and make sure that the problem was resolved in a timely manner.

Mobikwik, Freecharge and even Ola tried their hands at it but were getting nowhere. This was the time at which UPI was introduced. A government-aided trust layer, where Paytm had done all the handwork to earn the trust.

In no time, everyone including Google had a UPI app. The unassailable Paytm was left in the dust as UPI transactions soared to hundreds of billions of dollars amply aided by the demonetisation. Today, close to 10% of India’s GDP is transacted through UPI.

UPI much like Visa does not have an operational layer today. You need to be sufficiently bourgeois to acquire the license and you can set up an app.

Learning and innovation go hand in hand. The arrogance of success is to think that what you did yesterday will be sufficient for tomorrow.

~William Pollard

Having worked with startups for over 10 years now, I know that it is rather easy to engage in intellectual masturbation in an air-conditioned room. It is another thing to translate that into real-world impact.

In the case of UPI, the real-world impact was primarily delivered by demonetisation and the subsequent hardship that was imposed on many. In addition to that, all the “fintech” laggards who were in no position to catch up with Paytm got on the bandwagon and put thousands of people on the road to onboard shops and distribute their QR codes so their apps would become the preferred destination. Not to mention, offered insane discounts and cashback offers to users.

Now, the likes of PhonePe are figuring out how to monetise and all roads lead to debt.

By any metric UPI was a wild success. The government helped spread a trust layer and it has brought so many people who were previously unbanked in the banking net. Along with fintech, delivery was another segment that rose and rose over the last decade.

In January 2013, there were NO services for food delivery in India. There was no Amazon in India. Uber had not been launched in India and Ola was an inter-city cab service provider.

This changed rapidly and it created opportunities for retailers, wholesalers, restaurants and gig workers. Nobody is happy with the kind of commissions that Swiggy, Zomato, Ola, Uber or Amazon charge.

The question was - Can we do to delivery business what UPI did to transactions?

In 2021, a private company with the blessing of the government launched the Open Network for Digital Commerce or ONDC for short. The idea was that if restaurants, shops or even delivery networks were free agents an application layer could connect the restaurant or e-commerce companies with the people who undertake the delivery.

They imagined that if a store had a delivery fleet of its own, it could take care of delivery itself and if a consumer app brought the customer to the store, ONDC could effectively be the intermediate layer that enable the transaction. The trust layer.

Much like UPI, which connects all banks with the consumer app which in turn enables the consumer to transact.

The problem is trust.

In the case of UPI, the trust layer simply is the technology and it should work.

Have you been at a restaurant with only your mobile phone wondering if you will have to wash plates when UPI fails you? Or at the end of a cab ride with an irate driver who wants to proceed to the next trip but cannot because your payment is not going through?

UPI is far from perfect and fails when you least want it to.

The reason it has gotten as big is the network effect. It is also extremely safe, almost all of the frauds are socially engineered it is not like someone hacks the system and keeps bleeding your account. You have to enter the code of your own volition on your own phone. Also, despite the fact that it fails to deliver at times due to server issues, you will not lose your money.

ONDC by comparison has a human aspect to deal with when it comes to trust.

What would happen when your delivery boy does not show up? When he delivers the wrong item and leaves? When he calls you up and says he has a puncture and cannot come? This trust layer is far more complex.

Amazon runs the warehouses, the delivery fleets and the logistics from city to city. Replicating this will not be easy.

There is a huge operational layer at work. People, call centres and sometimes just absorbing the loss when the delivery guys go astray. ONDC just assumes this will all go away. It has taken Swiggy, Zomato, Flipkart and the like decades to perfect the operational aspects of the business. Drawing a line between customer service and the asshole who will call up and ask for a refund even though he has got the delivery.

Even if restaurants and the like get on this bandwagon for now, when they calculate the amount lost to all these kinds of “operational challenges” and money saved from not having to pay Swiggy or Zomato or whoever else; they are probably going to want to stick to the aggregators.

Rope in the Indian Post for some products.